This exhibition marks the end of James Hugonin’s most recent series, collectively titled Fluctuations in Elliptical Form, a sequence of eight paintings begun in 2015 and completed at the end of 2021. Seven of the eight paintings are reunited in this exhibition.

For the last four decades, James has pursued a deeply personal way of making pictures in which small marks of wax-thinned oil paint are applied across an underlying grid, with each painting taking, on average, a year to complete. For almost all this time he has lived and worked in his native Northumbria, in a home shared with the artist Sarah Bray, who he met as a fellow student at West Surrey College of Art and Design, Farnham, in 1973. They live on the edge of the Cheviot Hills, on the English side of the border country with Scotland, in a house on a hill looking towards Lindisfarne and the light of the North Sea. Over the years his deeply subtle, time-based paintings have evolved from works of spectral translucency, in which the light of the Northumbrian landscape is channelled into colours so thin that they almost completely disappear, to the tonally weighty marks of more solid colour that characterise more recent paintings.

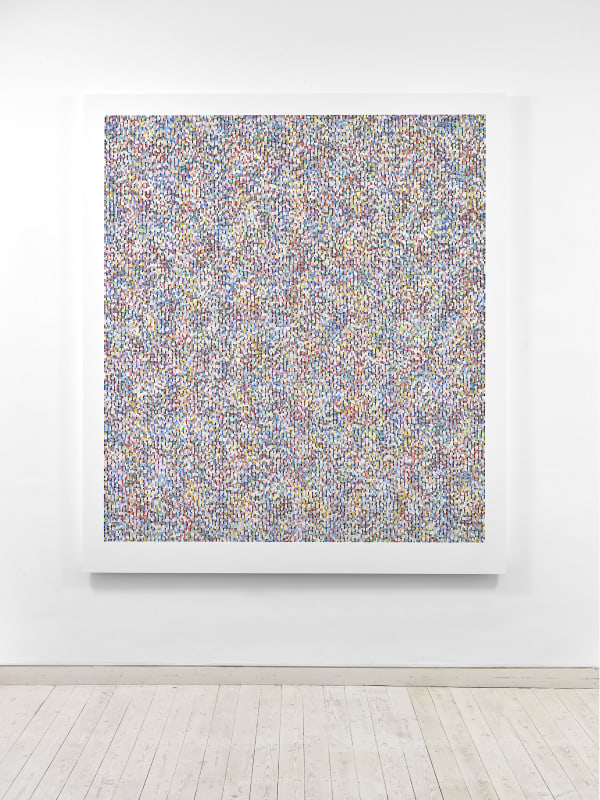

The Fluctuations in Elliptical Form paintings, each at a little over two metres in height, are the largest paintings of James’s career, and the shift in scale matters - making the experience of the work slightly larger than our ability to take it in – creating an expanse of shimmering marks over which the eye moves, and the brain sinks. That passage between eye and brain is where these extraordinary paintings operate like no other, offering a slight sense of hypnosis and an inbuilt gentleness of pace that somehow determines the speed at which we see them.

As the neuroscientist Anya Hurlbert writes in a new book being published to accompany this exhibition:

“Shimmering is the adjective most readily applied to James Hugonin’s paintings. There is an extra dimension to the flat painted surface that appears like lustre, like the movement of light on water from different angles. The movement feels like magic. Such illusory motion in static images with repeating patterns is well known in the science of visual perception, yet still not fully explained. Tiny eye movements – microsaccades – seem to drive the sensation.

In Hugonin’s paintings, the periodicity of the patterning of the tiny colour elements likely prods the mind into finding correspondences between the slightly different images of a cluster in the two eyes. The visual brain calculates a virtual depth based on these correspondences. Then the eyes move, and another cluster comes into view, with a different virtual depth. These minute fluctuations in depth of incidental clusters appear as moving lights across the surface. This is my speculation, unvalidated, incomplete, but fueled by my fascination with the glistening, rhythmic colours.”

These are systems-based paintings that accept, indeed celebrate, the human fallibility that is at their heart. The system is essential, but it is never in complete control, so that the closer you look, the more individual, and indeed hand-made, they become.

The exhibition continues until 26 March and will close with a live performance of Julius Eastman’s music for four pianos Gay Guerrilla. Further details of this performance will be available from the gallery nearer the time.

The book Fluctuations in Elliptical Form, with contributions by Anya Hurlbert, Chris Yetton and Alex Charrington, will be published in early March.